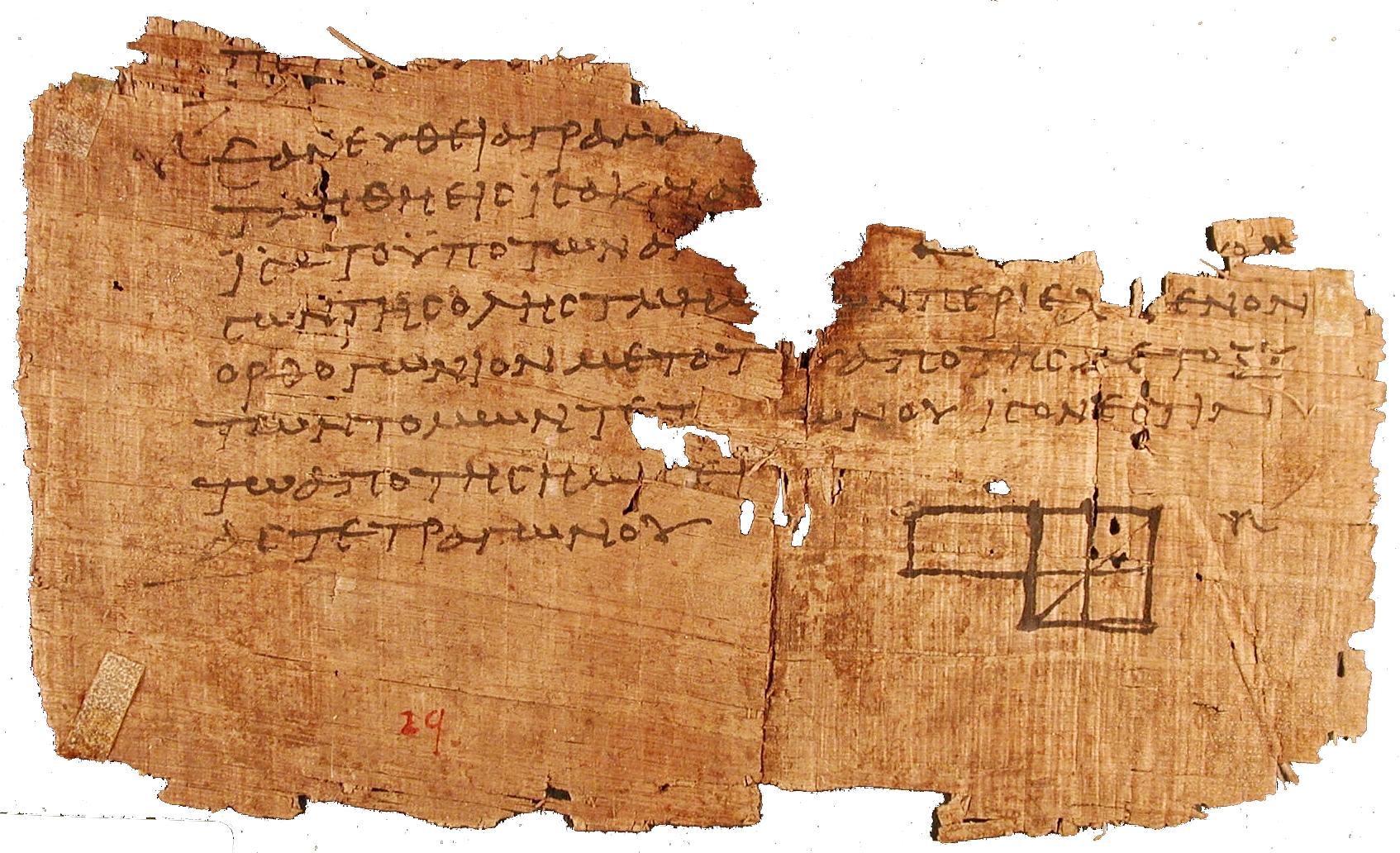

Paper was invented by the Chinese by 105 AD during the Han Dynasty. The word paper is etymologically derived from papyros, Ancient Greek for the Cyperus papyrus plant.

The Gutenberg Bible was the first major book printed. A single complete copy of the Gutenberg Bible has 1,272 pages; with 4 pages per folio-sheet, 318 sheets of paper are

required per copy. The handmade paper used by Gutenberg was of fine quality and was

imported from Italy.

Although cheaper than vellum, paper remained expensive, at least in book-sized quantities, through the centuries, until the advent of steam-driven paper making machines in the 19th century, which could make paper with fibres from wood pulp.

Together with the invention of the practical fountain pen and the mass produced pencil of the same period, and in conjunction with the advent of the steam driven rotary printing press, wood based paper caused a major transformation of the 19th century economy and society in industrialized countries. With the introduction of cheaper paper, schoolbooks, fiction, non-fiction, and newspapers became gradually available by 1900. Cheap wood based paper also meant that keeping personal diaries or writing letters became possible and so, by 1850, the clerk, or writer, ceased to be a high-status job.

The original wood-based paper was acidic due to the use of alum and more prone to disintegrate over time, through processes known as slow fires. Documents written on more expensive rag paper were more stable. Mass-market paperback books still use these cheaper mechanical papers (see below), but book publishers can now use acid-free paper

for hardback and trade paperback books.

Acid–free paper

Acid-free paper is paper that infused in water yields a neutral or basic pH (7 or slightly

greater). It can be made from any cellulose fiber as long as the active acid pulp is eliminated during processing. It is also lignin and sulfur-free. Acid-free paper addresses

the problem of preserving documents for long periods.

Today, much of the commercially produced paper is acid-free, but this is largely the result of a shift from china clay to (cheaper) chalk as the main filler material in the pulp: chalk reacts with acids, and therefore requires the pulp to be chemically neutral or alkaline. The sizing additives mixed into the pulp and/or applied to the surface of the paper must also be acid-free.

Alkaline paper has a life expectancy of over 1,000 years for the best paper and 500 years for average grades. The making of alkaline paper has several other advantages in addition to the preservation benefits afforded to the publications and documents printed on it. Because there are fewer corrosive chemicals used in making alkaline paper, the process is much easier on the machinery, reducing downtime and maintenance, and extending the machinery’s useful life. The process is also significantly more environmentally friendly. Waste water and byproducts of the papermaking process can be recycled; energy can be saved in the drying and refining process; and alkaline paper can be more easily recycled.

The Future of paper

Some manufacturers have started using a new, significantly more environmentally friendly alternative to expanded plastic packaging made out of paper, known commercially as paperfoam. The packaging has very similar mechanical properties to some expanded plastic packaging, but is biodegradable and can also be recycled with ordinary paper.

With increasing environmental concerns about synthetic coatings (such as PFOA) and the higher prices of hydrocarbon based petrochemicals, there is a focus on zein (corn protein) as a coating for paper in high grease applications such as popcorn bags. Also, synthvetics such as Tyvek and Teslin have been introduced as printing media as a more durable material than paper.

Tyvek

Tyvek is a brand of flashspun high-density polyethylene fibers, a synthetic material. The material is very strong; it is difficult to tear but can easily be cut with scissors or a knife. Tyvek superficially resembles paper (for example, it can be written and printed on). Tyvek is used by the United States Postal Service for some of its Priority Mail and Express Mail envelopes. New Zealand used it for its driver’s licenses from 1986 to 1999 and Costa Rica, the Isle of Man, and Haiti have made banknotes from it. These banknotes are no longer in circulation and have become collectors items.

Teslin

Teslin is a synthetic printing medium manufactured by PPG Industries. Teslin is a waterproof synthetic material that works well with an inkjet printer, laser printer, aerosol jet, or thermal printer. Teslin is also single-layer, uncoated film, and extremely strong. The strength of the lamination peel of a Teslin sheet is 2-4 times stronger than other coated synthetic and coated papers.

Electronic Paper

Electronic paper, e-paper and electronic ink are a range of display technology which are designed to mimic the appearance of ordinary ink on paper. Unlike conventional backlit flat panel displays which emit light, electronic paper displays reflected light like ordinary paper. Many of the technologies can hold static text and images indefinitely without using electricity, while allowing images to be changed later. Flexible electronic paper uses plastic substrates and plastic electronics for the display backplane.

The future of Electronic Paper

Thirty-five years in the making, electronic paper is now closer than ever to changing the way we read, write, and study — a revolution so profound that some see it as second only to the invention of the printing press in the 15th century. Made of flexible material, requiring ultra-low power consumption, cheap to manufacture, and—most important—easy and convenient to read, e-papers of the future are just around the corner, with the promise to hold libraries on a chip and replace most printed newspapers before the end of the next decade.

References

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_paper

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gutenberg_Bible#Pages

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Acid-free_paper

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paper#Future_of_paper

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tyvek

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Teslin_(material)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Electronic_paper

Iddo Genuth: Τhe future of electronic paper (http://thefutureofthings.com/articles/1000/the-future-of-electronic-paper.html)